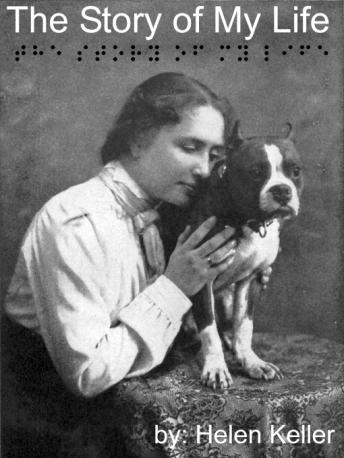

It’s certainly happened before, the most famous example being Helen Keller’s bestselling memoir The Story of My Life (1903). But as a DeafBlind poet who doesn’t read print, Clark finds himself in a tricky position: he’s written a book that he can’t read. The presentation is unsurprising, standard it’s how the world typically encounters books. (It’s also, I should note, available as an e-book, which presumably allows text to be manipulated into alternative formats). Like other poetry books, How to Communicate has a hard cover, a spine, and pages of printed verse. We can give foreign things new purposes, which may be slightly or extremely different from their original intent.” Clark’s challenge is answered, in part, by his first full-length collection, How to Communicate. Instead, we can leave those things well alone where they belong, or, moved by possibilities, we can transgress, translate, and transform them.

Rather than replicate seeing and hearing people’s worlds, Clark explains: “We would do well to abandon the pretense that it’s possible to reproduce base things in realms other than those that gave birth to them. Clark instead takes his cue from DeafBlind architect Robert Sirvage who says, let’s no longer ask “How do we make it more accessible?” but ask instead, “What feels beautiful?” While “Oralism” foregrounds the normalizing demands Howe places on Deaf pupils, Clark imagines a more diffuse language, one that embraces disabled people’s collective experiences. Access is usually, he tells us, a one-directional enterprise focused on inclusion: let’s let them (disabled folks) have what we (abled folks) have. This poetic critique echoes one made by Clark in an essay published in McSweeney’s in the fall of 2022 that departed from disability studies scholars’ and activists’ emphasis on access. But DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark’s poem “Oralism” presents a different historical record: emphasizing the abuse blind students suffered under Howe, who demanded that young pupils cover their “malignant eyes” with ribbons and “forget words.” Referring to the 19th-century letter board for blind writers-which allowed students to draft manuscripts by hand so that they would be legible to sighted readers-Clark says of Howe: “He made us write letters we could not feel.” The first director of the Perkins Institute for the Blind, Samuel Gridley Howe, was praised for his purported advancements in blind students’ education.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)